Story:

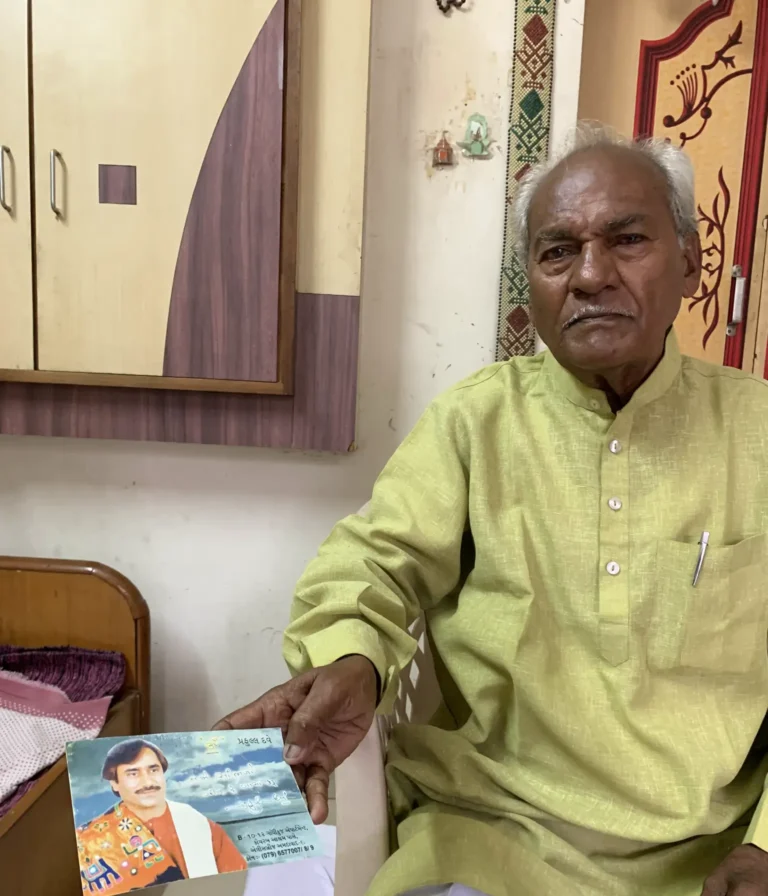

I was born in 1941 in Hyderabad to a Scottish-Indian family, and named Maryam Haqqani. I was called Munni at home by my family when I was little. My father was a powerful landlord, the cousin of Laiq Ali, the Prime Minister of Hyderabad at the time. My mother, Eva Matthew Watt, was a homemaker and a relative of Sir Robert Alexander Watson. My parents met while studying at Glasgow University.

The smell of jasmine evokes images of my childhood. In the summers, our beds would be covered in jasmine flowers to keep the room fragrant and cool. I also fondly remember my aya (nanny). In the evenings, we would play in the vicinity of one of my father’s textile factories and would see the gigantic sugar plantation near the factory.

My siblings and I had no idea about the implications of Partition. From 1947, until police action in Hyderabad in 1949, we did not notice any change in our lives. Our elders did, however, say that the events may have affected us at some subconscious level. In 1947, my siblings and I were taken to Scotland by our mother, to meet with our ailing grandfather. In 1949, I returned to Hyderabad, and was enrolled at the British-run Mehboobia School. It was during the time I was in school that I began to feel some tension in our city. Firstly, we were appalled at having to learn Sanskrit and Hindu greeting phrases at school when the main spoken languages of Hyderabad were Urdu and Persian. Second, we started hearing news of ‘police action’ and of ‘Hyderabad going under siege’. I heard many horror stories, of havoc, raping, killing, looting. One night, thousands of rioters gathered around the Goshamahal Baradari assembly building and started chanting slogans. My entire family was inside. My siblings and I were instructed to sleep on the mattresses at the landing of the mansion, the only place that did not have any windows. I heard my parents talking with each other about a pistol my mother was carrying. I remember my father asking my mother how she was going to defend herself with one pistol against thousands of angry people outside. She told him that the pistol was not for them, but for killing us, the children, in case the mob was able to breach the mansion.

Later that year, when my family felt that conditions had become too unsafe, we left with my father’s briefcase. He drove us to the railway station, and we boarded a special train to Bombay (now Mumbai). From Bombay, we took the evening flight on one of the Dakotas and flew to London. The year was early 1950. We stayed in London for two years, and then relocated to Karachi in 1952. As Hyderabadis, we were living under the fantasy that no matter the division of countries, Hyderabad would always remain Hyderabad since it was the largest and most independent princely state at the time. It was not a question of us leaving one country and going to another. In our heads, we thought that we had left Hyderabad, and settled in Karachi. When our father announced that we were going to Karachi, he did not say we were leaving, instead, he told us that since we had a fairly good time in Karachi, we were going to settle there. From a child’s perspective, we were not leaving our country to be in another country.

I resumed my schooling in Karachi at the Saint Joseph School, and subsequently Saint Joseph College. My father took giving up his homeland as something that was inevitable, and he strongly believed in letting go of things that were inevitable. My mother, on the other hand, could not get over these changes all her life. She compared each and every aspect of life in Karachi with what we had in Hyderabad.

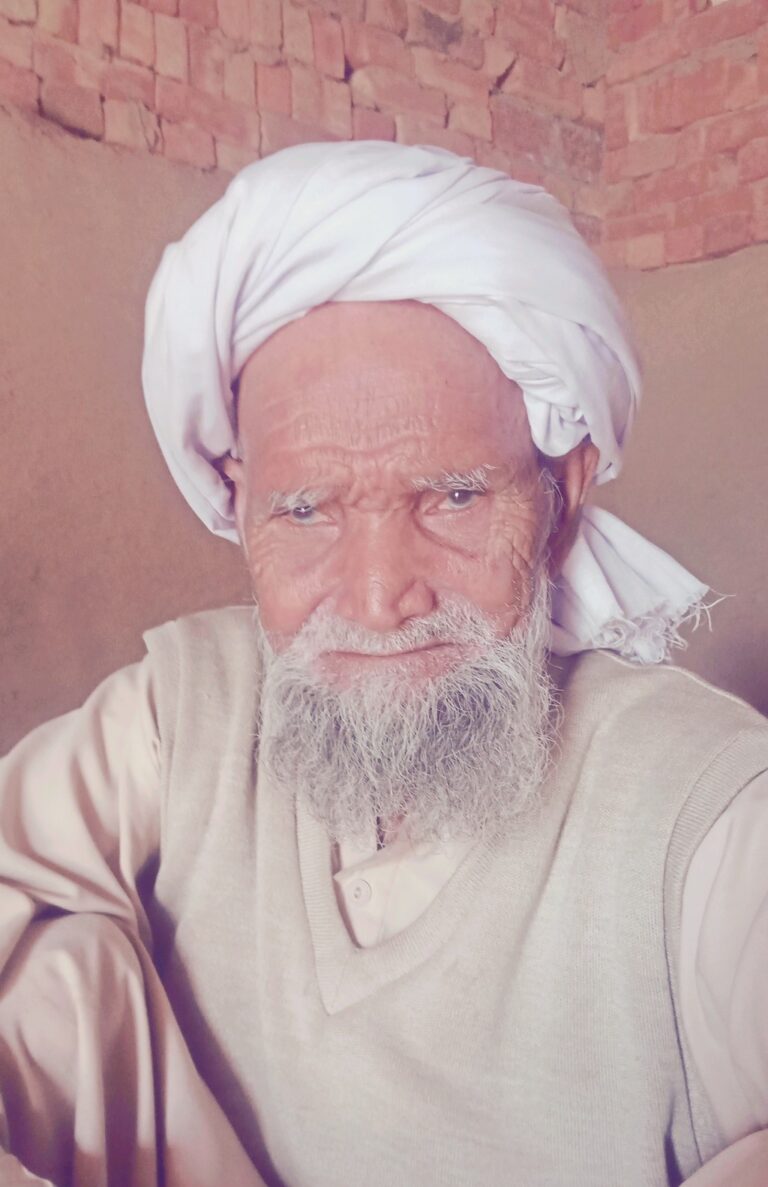

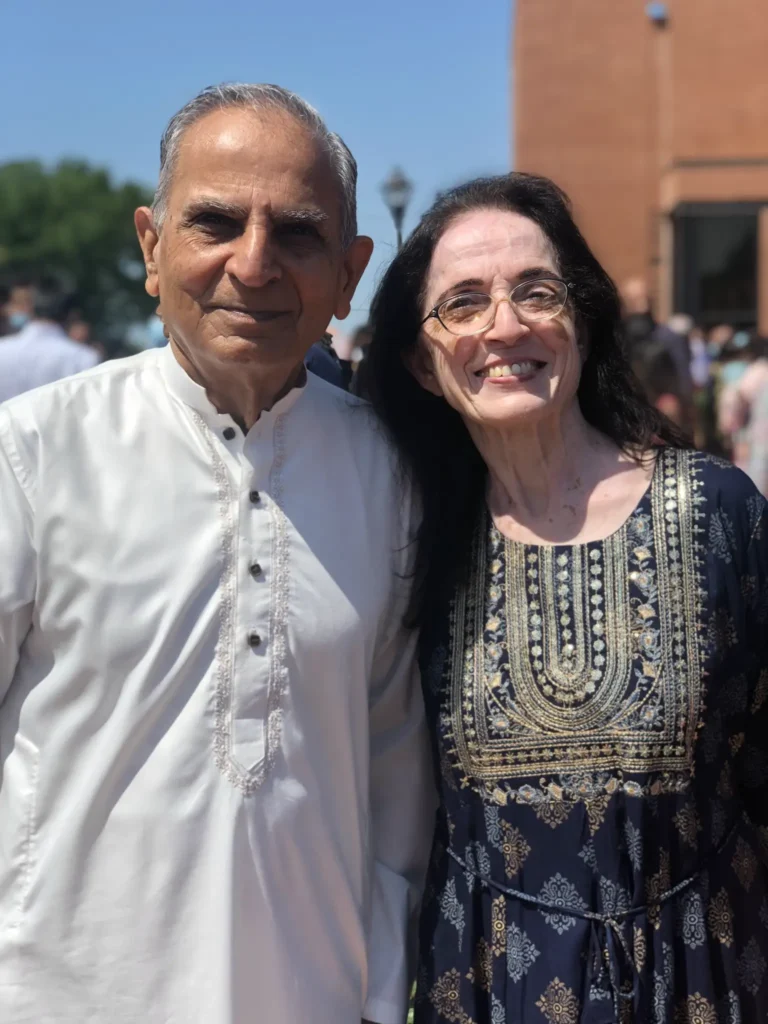

I met my husband while taking German language classes in 1960, and I married him three months later in December 1960. We married at Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where I now live with him. We had three daughters and a son, who has passed away.

After returning to Karachi in 1967, My family and I travelled to Brazil, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Iran, Australia, Germany, and then finally to India in 1992. My husband was a diplomat, and would travel frequently without us for his work, and was brought into the line of danger many times. On many days, we did not know whether he was alive or dead. In 1996, we settled in Peshawar permanently. I started my own farming business in 1988, and continue to manage it today.

Now, when I tell people that I am from Hyderabad, Deccan, people automatically assume my nationality. This is the dilemma you face, when you are forced to leave what has been your family’s home for generations, for centuries, the place where you were born and made to think is yours forever, you remain a refugee for the rest of your life. It never goes away. I am living in a home that I absolutely love, but I will always know that this is not where my roots are.