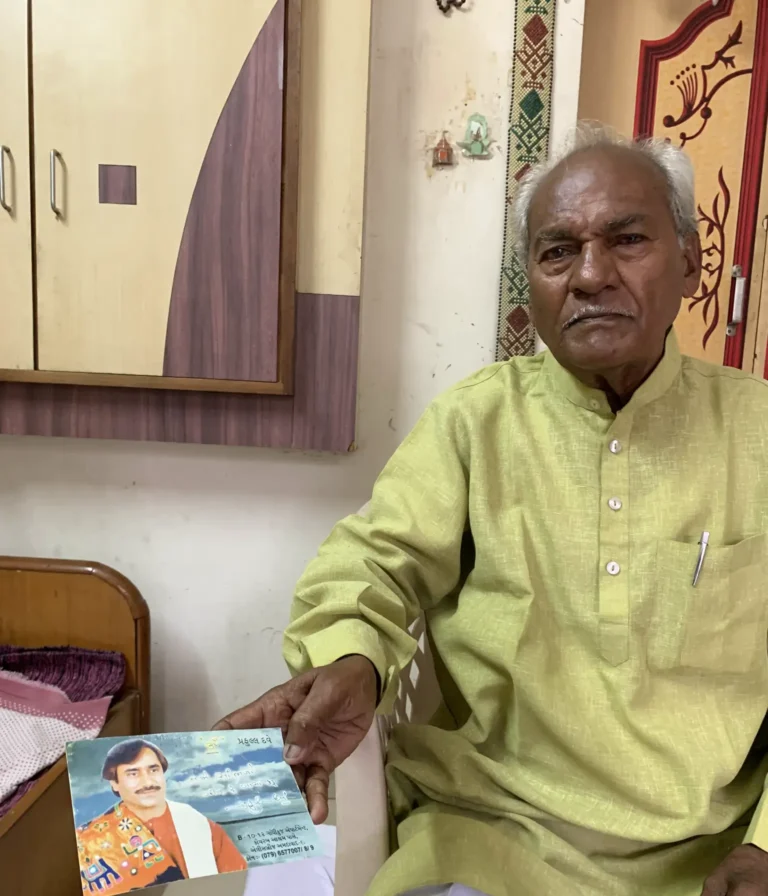

Khushi Muhammad Jut, son of Gainda Jut of the Mallan Haar Gotra, was born at the village of Aloona Tola in the district of Ludhiana,

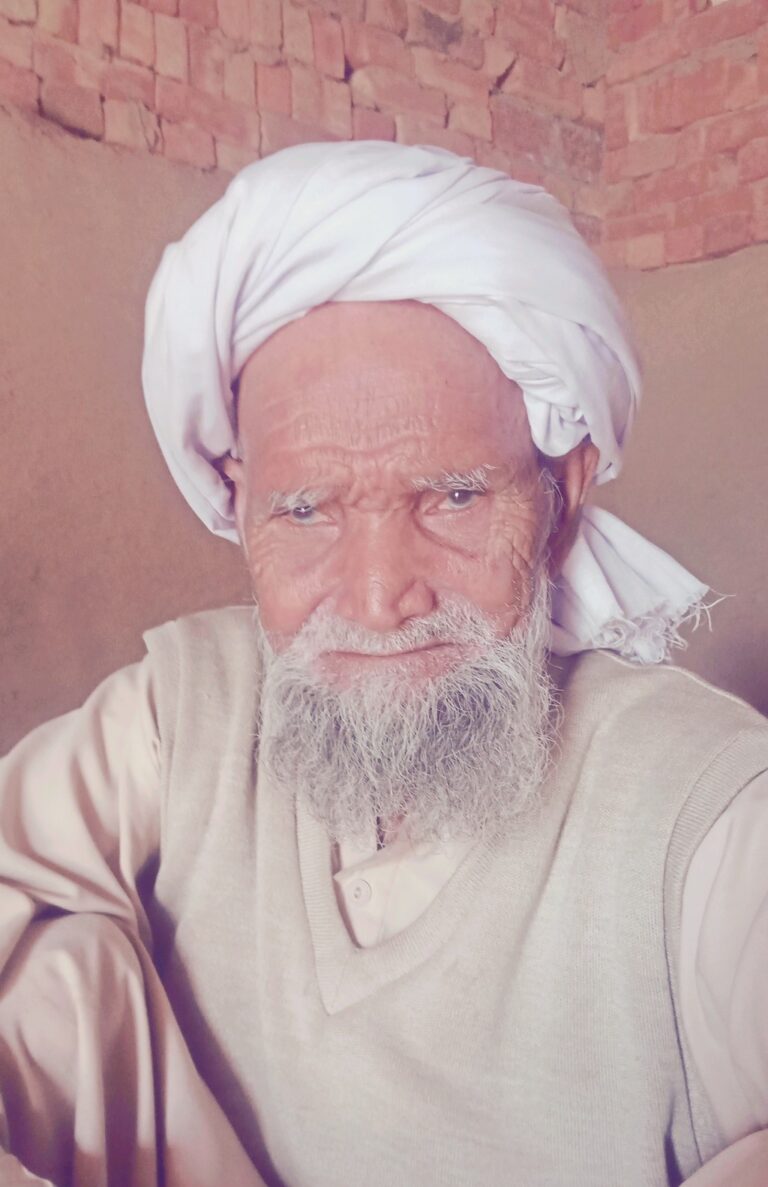

Oral Historian: Muhammad Sarfraz

Camera Person: Muhammad Sarfraz

Summary:

Khushi Muhammad Jut, son of Gainda Jut of the Mallan Haar Gotra, was born at the village of Aloona Tola in the district of Ludhiana, now in the Indian Punjab. He migrated to Chak 302 GB Bhatti Chak in 1947 when the Partition of India took place. He shared his memories, saying that he was seven years old when Pakistan was created. Talking about his village he recalled that Deva and Nasrali were the villages of Sikh majority closest to Aloona Tola. They were living in a village of mixed community with both Sikhs and Muslims. There was one village headman– called Ibra– for the Muslim community there and one zaildar (officer in charge of a revenue and administrative unit of a group of villages)– called Sher Singh– was for Sikhs in the village.

He said he had not seen his grandfather, Soba. One of his uncles, Ghulam Haider, was living with them. His maternal grandparents hailed from Sirhind, but he does not remember their names. He does not remember the name of one of his aunts. His mother, Fatima, was the mother of three children. The elder son was Hassan Muhammad and Zenat was his sister; she was the eldest one. He said his father’s elder brother lived with them all his life, he never went to his maternal grandparents.

Talking about his home, he recalled that his home was made with Ghilafi (a type of brickwork) walls and constructed on five marla (equivalent to 272.25 sq. ft. per one marla) of land. There was only one big room. A hawali (separated living space for animals) for the animals was separate. Women were to fetch water from the well in the village, close to the gurdwara (Sikh place of worship); there was a place for every community to fill their pitcher. They owned two pairs of oxen, and four buffalos and a camel to run the well. The wells were named by the family that owned it; Nawan Khu was owned by his elders. He praised the water, saying it was so nourishing and powerful. They owned a large amount of land and most of the land was arid. All kinds of crops grew there with rain water; chiles, sugarcane, and peanuts also grew there. Many toots (mulberry) trees were there.

Talking about the village streets, he said they were wide enough and were dusty. Most of the village was built with mud and only the homes of the zaildar were made with baked bricks. There were other working communities also living there. There was a mosque (Muslim place of worship) in the village for the Muslims; even a few Muslim families are still there. He may have eaten karah prasad (a variation of wheat-based halwa) distributed outside of the gurdwara; Muslims were to sacrifice only goats and sheep. They were to offer Eid prayer on the open ground.

There was a pond on the north side of the village. A peepal (sacred fig tree) tree was close to the takia (general meeting room for elders to talk) in the village. Hindu Khatri (caste engaged in mercantilist professions) were shopkeepers on the side of the Sikhs; he does not remember their names now. There was a faqir (a man who kept fire alive using cow dung cakes as fuel) in the takia; he was to keep the fire alive for the villagers to refresh their hookah and he was given wheat in the season. A school was in the village for the boys. He went to school for a month when Partition took place. He used to sit on mats. Some boys used to go to Nasrali village for high school.

Talking about relations with other communities, he said they were living in good relations with them. A dry ration was exchanged on occasion and was known as pakki roti (a pressure cooked wheat flatbread). He said one Sikh was a friend of his elders. He played games like gilli danda (a sport played with two sticks, its rules bear similarities to cricket and baseball), hide and seek, and swinging on the trees. The Chamar (caste often associated with leatherwork and agriculture) were helpers; the dead animals were picked by them and they were to skin the animals for leather. A few were also cobblers. He does not remember any weavers there. He said roonga (a complimentary gift– often sweets– given by a shopkeeper to a customer, especially to kids) was given to young customers by the shopkeepers.

He also enjoyed festivals at different villages. Jarg was famous for the festival held there; he went there with his elders. Dogar (a Punjabi people of Muslim heritage), Chhaparias (a clan of Jats), and Shareef Ragi (a popular Punjabi folk singer) used to sing there. Only anna (equivalent to 1⁄16 of a rupee per one anna) was given to him for spending there. Jugglers used to come in the village and elephants used to come in the village. The blacksmith, Sardar Deen, had a bicycle. The only gramophone was in the village.

He barely remembers anything about the voting that took place there. Talking about Partition, he recalled that his elders used to say, “For generations we have been living here, how can we leave our homes?” Pakistan may have been made but it was not for them. Soon Sikh migrants started to come there insisting their brethren push the Muslims out of the village if they are not willing to leave their home; they even planned to attack the village. When his father’s friend from Jandali tipped them off to leave the village by sending a horseman, he could not be sure if they would convert them all to become Sikhs or that they would kill the Muslims at the village. And so his father collected them and hid in the field near Nasrali at the land of Shadi Singh. Sikhs attacked the village, asking them to get together and saying they were to become Sikh if they wanted to live. When many Muslims were found together, they started to kill them. Young girls were pulled out and many women were slain. His mother and one aunt were asked to hide themselves in the home somewhere, so she was also among those women walking in the street of the village. When she found the chance to hide herself in the house she found the door open. When the sun set, his uncle went to live with his in-laws at a village in the state of Malerkotla. His father took them to the village of Deva and they stayed there for a night. The next day they went to Jandali and stayed for many days there at the home of Amla Singh, the man who sent the horseman to tip them off. He advised them to live at the camp in the Khanna locality of Bhattian; half of the family went to Bhattian and half of them went to live at a village in the state of Malerkotla. He recalled they were in the camp when the village of Ikolaha was attacked and people took refuge at Bhattian. From there they moved in a caravan to Sirhind at Rauza Sharif (a gurdwara). He took them to a camp at Ludhiana and he provided them rations while they stayed in the camp.

He recalled his mother, Fatima, and added that she was with his aunts. She was holding her daughter when she escaped and a Sikh fired a shot which hit her in her elbow. His mother lowered herself into a well and stayed there for a long time. When she felt everything was over, she came out and stayed in the barn, covering herself in the mound of haystack. When Gainda came to know about his sister-in-law, as she was alive with her daughter, they looked for Fatima. She was found hiding in the haystack of the Chamar house and was working as their helper. He was with his mother and father when stayed in the camp at Ludhiana.

The camp was in the center of the GT Road, (Grand Trunk Road, one of Asia’s oldest, longest major roads connecting Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent). In those days rain was falling like cats and dogs. They stayed in the open sky and the army was escorting the people in the camp. They sat in the goods train that took them towards Pakistan. Sikhs were seen during the day looking for a chance for a kill. The Gurkha Army (Nepalese soldiers who served the British Army and later the Indian Army) walked beside the train and did not let anyone attack. They did not even let anyone drink water from the ditches, so his father gave them water from the hooka to wet their dry lips. Then they stopped at safe terrain, but he suffered from fever. He does not know from which side they entered Pakistan, but they reached Lahore. The same train took them to Lyallpur (now Faisalabad), and they stayed in the camp there. They could not find the train so they started to walk beside the railway line. They found the train when they were walking close to Pakka Anna Railway Station, then in that train they came to Toba Tek Singh. From there they came to Chak 345 GB at the house of Sher Muhammad, as one of Gainda’s cousins was married there. They stayed for a month with her and then they came to live at Chak 302 GB Bhatti Chak. One cousin of his father was in the army. He came with a truck to pick up his family members, but sadly, most of his family was killed at the village. He came to know some of his members reached Malerkotla, and he found them and they sat with him on the truck. They entered Pakistan through Ganda Singh Wala; he was to leave his vehicle at the border. They reached Kasur and from there they reunited at Chak 345 GB, before Khushi Muhammad reached there.

Police used to come into the village to distribute looted articles. They found a cot and came to live at the Chak 302 GB. They were given an acre per person and later their property claim was verified. The land owner found their claimed property and their property was increased later. They found a home there. He said the village was built with mud and only the zaildar’s home was made pakka (permanent housing made of stone, brick, cement, concrete, or timber). Water was drawn from the well beside the pond. He was not sent to school here; instead he was to help his parents. His mother died before his father.

His new life started and he never looked back. He got married when was well matured and in those days elders were to decide the future couple. Sweets were served along with boiled rice; raw sugar was poured upon the rice along with Desi ghee (clarified butter). Ragi was called to sing songs by those who could afford it and a brass band was often called to play music. He got married at Chak 345 GB. He sat on a mare and carts were used to travel. In those days women were not allowed to go with them. They gave gold jewelry and silver was also given. Cloths for the bride were also bought from the city. They came back with his bride, and women welcomed the bride and oil was poured on the door steps. He was blessed with sons and daughters. He sent them to school and they are leading their own lives. One of his sons used to visit India to meet them at Bauri village. They went back to India after marrying their daughters.

He said partition benefited some and some faced loss. But they have become selfish; peoples of this area are dry in nature.