Story:

I was born in 1926 in Mianwali Bangla, Daska Tehsil, in the Sialkot District of West Punjab. My father, Tarlok Singh, was an accounting officer in Lahore, and my mother, Balwant Kaur, was a homemaker. I have two sisters and a brother. I completed my high school education in a government school in Lahore, where I had a favourite teacher named Budhwant Kaur. I know Hindi, Punjabi, and English. I was fond of doing work, and me and my best friend, Harbansh Kaur, sat together doing embroidery and knitting. I enjoyed the Basakhi fair where my friend and I ate lots of golgappas (a bite-sized crispy snack). I liked the justice system that was in place during the time of British rule.

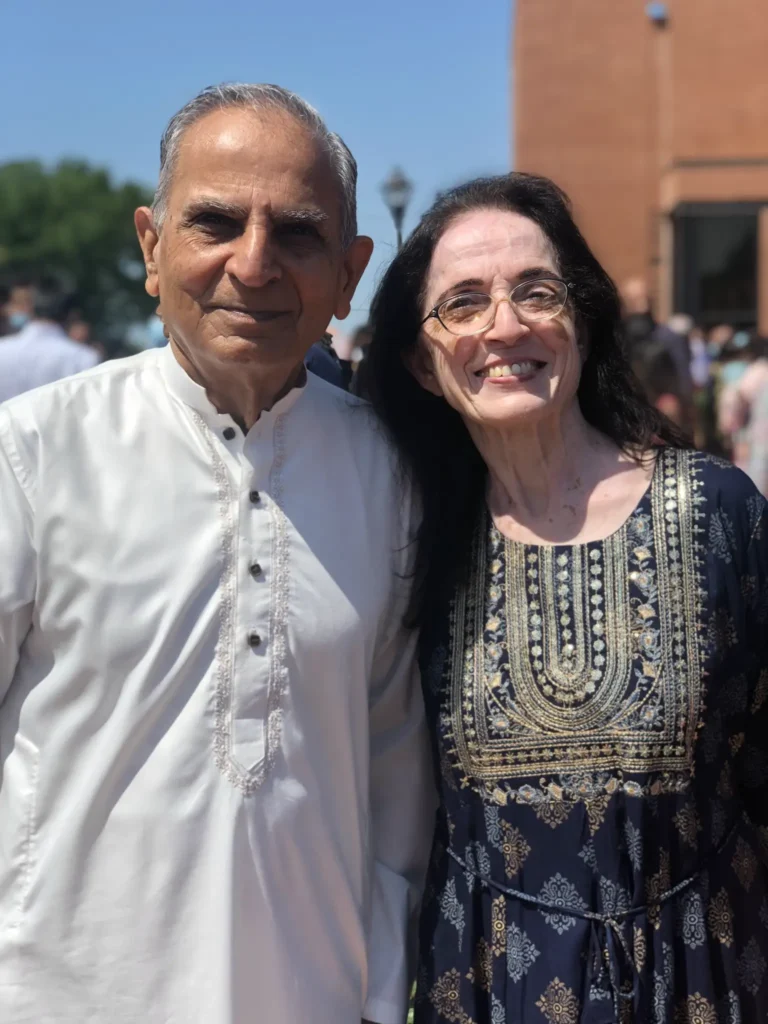

At the time of Partition, I was 21 years old and already married to Jaswant Singh Sandhu, a captain in the army who later became a Lieutenant General, and died in 1980 as Vice Chief of Army Staff. My husband came to the aid of over 100,000 people in August 1947. He was on leave at the time, and we, along with our baby son, Ardamanjit Singh (who later became a Major General), went to his village of Rampur, Wadala Sandhuan. Seeing the situation become increasingly dangerous, he contacted his superior, a British colonel in Sialkot. The colonel told him to get his family out immediately, and provided him with a truck, a jeep, rifles and ammunition, and a couple of soldiers to assist him. My young 22-year-old husband, Captain Jaswant Singh Sandhu, had asked permission to run a camp to help evacuate other helpless people who wanted to migrate. After receiving permission, he quickly returned to his village where he found a huge gathering of neighbouring villagers. They had gathered after they heard a “ganj machine,” a term they used for machine guns and rifles. The villagers knew that Jaswant’s father had served in the Indian army with honours, including a commendation for bravery from Sir Winston Churchill. Throughout the night other neighbouring villagers poured in, and every house in the village prepared food for their neighbours. Jaswant also began running rescue missions, as people came to him pleading for help to get their families and friends to safety.

That night Jaswant broke the news to his whole family that we would have to leave in the morning with minimal belongings, as he wanted to use the vehicles for evacuating people, and not possessions. His mother started crying loudly. Our son, some siblings, aunts, and uncles, and I were sleeping on the terrace that night when it started to rain. While rushing down the slippery steps, I fell down with baby Ardamanjit in my arms. Luckily Ardamanjit was unhurt, but I fractured my tailbone. The next morning I was made to lie down in the truck when we began our journey to Daska. All night, groups of men were organised as gatekeepers and guards at the most vulnerable points of entry into the village. Jaswant used his military skills to deploy the men after mapping out the area and its surroundings. He already had experience in active combat, having served in Burma during World War II. He used his training and experience to rescue and safeguard the villagers who were coming in increasing numbers for help. Over the course of several days, thousands gathered and Jaswant got many others safely to his village. An attack on the village was thwarted.

On our last day in the village, Jaswant and our family gifted our buffaloes and other livestock to our trusted domestic and farm helpers. One name that I never forgot was of a loyal worker called Bagga. Jaswant organised the convoy, with men lined up at various points for maximum security. As we exited the village, some mobs hiding in the fields attacked us but were foiled when the soldiers started firing to deter them. Barely a few kilometres into our journey, we were stopped by some villagers begging us to wait for 15 minutes so they could round up the rest of their villagers and neighbours. Jaswant agreed and soon we were joined by about 5,000 more people. The convoy moved on slowly, with Jaswant and his soldiers using their army training to get people safely to Daska. Halfway through the journey, we were again stopped by villagers requesting to join the convoy, so once again Jaswant stopped and thousands more joined us. When we made it to Daska, Jaswant organised a camp for the thousands he had rescued and brought with us. Each day thousands more would arrive, and some were rescued from villages close by whenever word arrived that people were holed up in their homes, unable to venture out for fear of attack.

During that time, riots were taking place everywhere, with rioters coming in large groups while beating drums. Young Jaswant, with a couple of soldiers, undertook a daily mission to save people. Often when he arrived at a village, he knew that women were ready to take their own lives if they were threatened by attackers, so they would not leave their homes. To prove that they could trust him, he would ask them to look out a window as he removed his turban to reveal his long hair underneath, thus reassuring them that he was Sikh. Then the families would run out to him for help. He also learned that his sister-in-law, Swarn, and her family were unable to leave their ancestral home, so he took his soldiers and vehicles to her village. She also did not at first trust him, as they had never met. Again Jaswant removed his turban to prove his Sikh identity and relayed details about the family. The family then emerged and were taken to the camp at Daska. Swarn stayed with me, and we met each other for the first time. I, who was still on bed rest with my painful tailbone injury, was horrified when my husband would come home late in the evening with blisters on his feet. We moved temporarily into an abandoned house that had belonged to a Dr. Aroor Singh, who had already migrated.

Most of the villagers did not practise good hygiene and were using the entire camp area as a common toilet, living, and food preparation area. Despite Jaswant’s best efforts, the villagers were not properly following his advice on separating the various areas, so he called a meeting of the heads of each village in the camp. He intentionally held the meeting in a particularly filthy area that had a strong stench. The village chiefs were surprised, and asked him why he did not choose a more sanitary place so they would not fall sick. Jaswant then made his announcement that if people expected to not fall sick, they must enforce hygiene and toilet rules. After that, he had no problems with sanitation and was able to organise separate areas for cooking, sleeping, toileting, and play areas for children. He then had entry points to each area guarded around the clock. Duties were given to all able adults and the village chiefs to carry out his orders.

Jaswant was a natural born leader with great compassion, excellent people skills, and outstanding bravery. He had a brilliant military skill set, and he always put human life over everything else. He ran the camp for one month. Word came to the camp that attackers planned to kill Captain Jaswant Singh Sandhu, followed by the rest of the camp. Two more assassination attempts were made on Jaswant, and both failed. Nothing deterred his relentless pursuit to save innocent people’s lives. One day he asked the groups to wait for him before seating themselves on a train while migrating. While the majority waited, some folks just rushed in and seated themselves anywhere they wanted. When Jaswant arrived, he had them disembark, which they did slowly and very reluctantly. He then explained how he wanted the seating arrangements done, but much time had been lost because of their impatience. Many of them grumbled, feeling they had lost their chance to get out fast. This journey should in normal times have taken a few hours but because of the various attempts to stop it and attack the occupants, it took two nights to reach Amritsar.

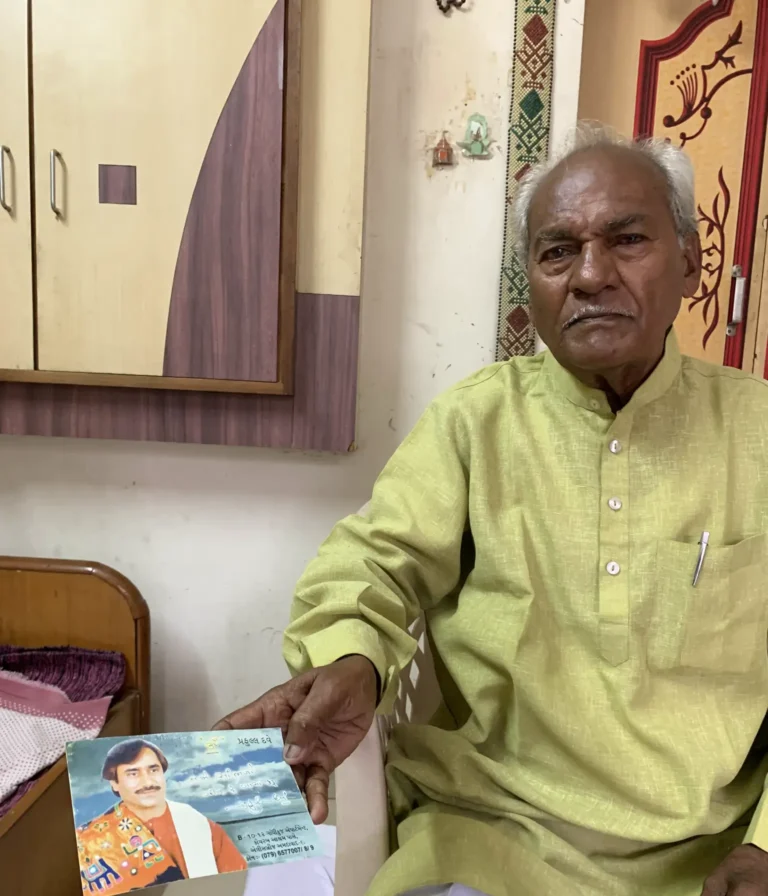

I finally breathed a sigh of relief, and happiness overtook me when I heard the call, “Jo Bole So Nihal” (Whoever utters the following phrase shall be happy and fulfilled), and the response, “Sat Sri Akal” (Eternal is the Holy/Great timeless Lord). I knew then that we had safely crossed the border. The government allotted land to our family in Banbhaura village near Malerkotla, East Punjab. When Jaswant and I returned to Bareilly in Uttar Pradesh, where he had been posted as a GTO (Group Testing Officer), he learned that the army had issued a statement saying one GTO was missing, as they had no idea where he was or if he was alive. The army knew of Jaswant’s great work, and he was awarded a chief commendation certificate by General K. M. Carippa.

I now get up at 9 a.m., take breakfast, and then read the newspaper or watch television. At 2 p.m., I go to the army grounds with friends. My message to the new generation is to take care of your elders and to not do drugs.